Climate-focused science fiction is not a recent development. Even if we were to reject all the works in which climate change is an unexpected benefit of thermonuclear war , or where the climate change is part of the process of terraforming other worlds , examples of classic works featuring anthropogenic climate change are not all that hard to find. It’s as though discussions of anthropogenic climate change date back to the 19th century and earlier … or something.

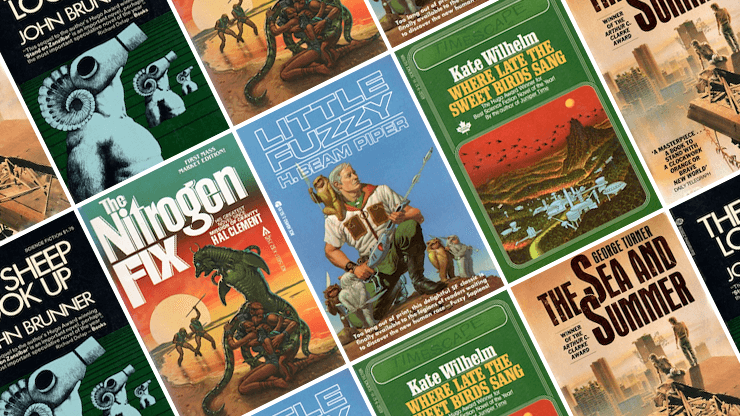

If H. Beam Piper is remembered at all these days, it’s as the author of a future history whose hopeful moments added up to a depressing portrait of historical inevitability over the long run, where happy endings are a matter of cutting the narrative short before grim reality reasserts itself. On rereading his popular first contact novel Little Fuzzy (1962) I was somewhat surprised to rediscover that the plot is set in motion by climate change. I was astounded that it was very specifically anthropogenic climate change caused by the Chartered Zarathustra Company’s Big Blackwater project.

He says there’s some adverse talk about the effect on the rainfall in the Piedmont area of Beta Continent. He was worried about it.”

“Well, it would affect the rainfall. After all, we drained half a million square miles of swamp, and the prevailing winds are from the west. There’d be less atmospheric moisture to the east of it.

The outcome? An opportunistic migration that brought Fuzzies, Zarathustra’s previously unknown natives, into the human-dominated region. It’s an event that transforms both the life of the prospector who first encounters them and the prospects of the Chartered Zarathustra Company, whose charter assumes that the world is unoccupied.

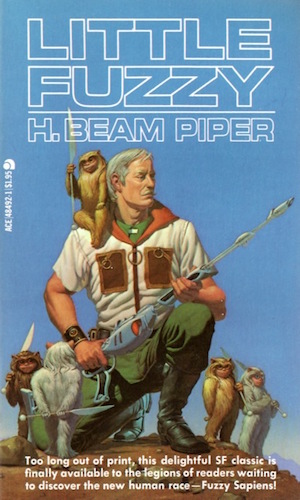

Each book in John Brunner’s Club of Rome Quartet presented humanity with some grand, specific challenge. In The Sheep Look Up (1972), that great issue is pollution, which manifests in all manner of delightful forms. Materials poured into the atmosphere have caused climate change and weird weather. Oh, and there’s acid rain, undrinkable water, crop failure, and ecological disruption on an epic scale. Nothing like the prospect of famine and the collapse of entire nation states to keep one from kvetching about the heat.

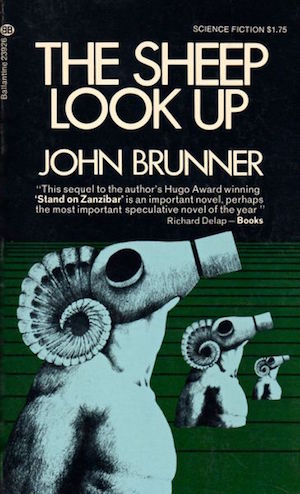

The characters in Kate Wilhelm’s Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang (1976) are focused on some short-term effects of human interference with the environment: exciting new diseases, crop failures, and most relevantly to the clone-focused plot, mass sterility. That humans also managed to warm the planet through their efforts becomes clear after the major die off; the climate improves when humans are no longer there to alter the atmosphere:

The winters were getting colder, starting earlier, lasting longer, with more snows than he could remember from childhood. As soon as man stopped adding his megatons of filth to the atmosphere each day, he thought, the atmosphere had reverted to what it must have been long ago [….]

In the future time in which George Turner’s The Sea and the Summer (AKA Drowning Towers, 1987) is set, it is far too late to avert or mitigate climate change. Australia’s society is divided into a few haves (the sweet) and a multitude of have-nots (the swill). The framing sequence, set long after the Greenhouse era, makes it painfully clear that any security the sweet may have is strictly temporary. Our civilization is doomed; people of the culture that arises out of the ruins of the Greenhouse era, a culture shown briefly, are baffled by what they know of our era.

None of the previous examples imagined changes as dramatic as those we see in Hal Clement’s The Nitrogen Fix (1980). Uncontrolled pseudolife (essentially nanotech in the form of alternative biologies, something that Clement envisioned long before Drexler popularized nanotech in less plausible form) has transformed the Earth’s atmosphere from N2 and O2 into various forms of nitrogen oxides. One of the side effects is a general, ongoing warming.

All Earth’s water was warm these days, except next to the still-vanishing pole caps. The acid seas had given off most of their dissolved carbon dioxide, and carbonate minerals were busily doing the same; greenhouse effect was warming the planet. Nitrogen dioxide, blocking some of the incoming radiation, was slowing the process, but where it would end no one could tell.

There are few humans left to be personally inconvenienced. Most of humanity is already dead.

No doubt there are other examples. Feel free to share them in comments.

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviews and Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.